In this second instalment in a new series of interactive walking maps, Daniel Neilson guides us through the history of Buenos Aires. View The Real Argentina’s whole Interactive History Walk of Buenos Aires in a single, larger map. (Also see our Interactive Foodie Walk.)

From its beginnings as a riverside settlement, to its present day status as one of the world’s largest cities 400 years later, Buenos Aires has fit an awful lot in. It’s been wealthy and glorious, it’s been battered and broke. Its life, as scientist Jared Diamond would say, has ben shaped by guns, germs and steel. Yet such is the city’s short, intense life, most of the influential buildings are still here to be seen and explored, the museums add essential detail, while the tombs of the country’s great, good and downright dastardly can still be seen in the great city of the dead: Recoleta Cemetery. The chronological nature of history doesn’t, of course, relate to the city plan, so there’ll be a bit of skipping around, but this walk will bring the city’s past to life and within the context of Buenos Aires in the 21st century.

In the Beginning

The pampas of the modern day province of Buenos Aires was not empty when the conquistadores arrived in the 16th century, but populated, albeit sparsely, by the hunter-gatherer Querandi. The history of Buenos Aires is one of settlement, however. Pedro de Mendoza, and a couple of thousand soldiers, founded Santa Maria de Buenos Ayres in 1536 in the area around Parque Lezama on the border between La Boca and San Telmo, and that’s where our tour begins. Handily, its also home to the Museo Histórico Nacional, a useful introduction to the city. It shows how the city was soon abandoned (the early settlers were reportedly killed and eaten), but the port became essential to the Spanish American plans, and in 1580 the city was ‘re-founded’. Buenos Aires was still a small port. It expanded slowly, as the silver from Bolivia and the market for leather and dried beef continued to grow.

The Rise

As you walk from Parque Lezama along Defensa, you’ll be heading through the early city. Looking up, you can see through the shabby exterior to the grandiose development underneath. This was once the wealthiest area in Buenos Aires, and the buildings are what earned its moniker the ‘Paris of the South’. At Plaza Dorrego, you’ll get a glimpse of a pre-1800 square. In the market at Defensa 179, you’ll see a vague approximation of a family home at this time. The buildings were abandoned in the 1870s after cholera and yellow fever epidemics struck within four years. The rich moved north to Barrio Norte and Palermo, then on the border of the great pampas. The poor moved into San Telmo and they stayed, in appalling conditions, to this day. On Alsina and Bolívar is the Iglesia de San Ignacio, the city’s oldest church dating from 1734. Near the church is the Museo de la Ciudad (Defensa 219) looks at the city’s architecture and has some wonderful old photos of the city around you.

The Revolution

At the end of Defensa is Plaza de Mayo, which has ben the scene of many events in Argentina’s history and still tends to be so. The original square was laid out in the 1580s by the city’s founder Juan de Garay (see his statue in the north east of the plaza). It was renamed Plaza de Mayo when the city celebrated Argentina’s independence on 25 of May, 1810. It has continued to be the gathering places for jubilant, or furious, hordes ever since. The Casa Rosada, the presidential palace, is where the fury of porteños is usually directed. It’s also from the lower balcony that Eva Perón (and Madonna) addressed the crowds. Look down however, and you’ll see a stark reminder of the dark period that followed the Peróns. Painted on the ground are the headscarves of the ‘Madres de la Plaza de Mayo’ a group of mothers who lost their children in the Dirty War, a period of appalling dictatorship. More than 30,000 people, many young, were ‘disappeared’. The Mothers, wearing white headscarves, would parade in silence around the Pirámide de Mayo… and still do every Thursday at 3:30. Their fight for justice is far from over. Another reminder is the bullet holes, caused by tanks in 1955 to overthrow Perón. The old building in the Plaza is the Cabildo, the city’s headquarters between 1580 and 1821 – the museum has some interesting artefacts.

After the Revolution

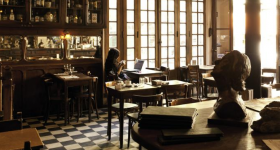

Avenida de Mayo is a wide boulevard with the Casa Rosada at one end and the Congreso at the other. It’s a symbolically important road – the presidents travel the ten blocks to Congreso to be sworn in. We’ll follow in their footsteps. The famous Café Tortoni, as part of the city’s fabric as the Casa Rosada, is along here on the right. When crossing the vast 9 de Juilo to the right you’ll see the much-loathed and much-photographed Obelisco (once covered in a giant pink condom for AIDS awareness). Continuing up Avenida de Mayo you’ll see the remarkable Palacio Barolo (and my old office) on the left at number 1370. It’s a tribute Dante’s Divine Comedy (I was fond of saying I worked in purgatory on the 10th floor).

The Plaza del Congreso is, frankly, run down, with many photos artfully avoiding the homeless shelters and ever-present protestors. The ostentatious Palacio del Congreso, completed in 1906, as a nod to the US Congress, is where the country’s politicians do their work. Call 4370-7100 to try and arrange a tour (but don’t get your hopes up).

Going Underground

We’re going underground now (this kind of ties up, trust me) to the cemetery (see!). Take Subte Línea A, the city’s first subway – some of the original wooden carriages still run here – and jump on Línea C at Diagonal Norte to General San Martín (download a Subte map here). As you emerge, the scene has changed again. The leafy plaza here has a vast statue of San Martín, one of the leaders of the Latin American independence movement, erected in 1862. Walk to the north end of the park, and you’ll see the Torre Monumental, a gift from the British once called the Torre de los Ingleses until the Falklands/Malvinas war.

From here, we’ll walk to our resting point, and that of a great many others. Walk to 9 de Julio, turn right and then left onto Alvear and past one of the city’s most expensive hotels, the Alvear Palace, to Recoleta Cemetery. This is perhaps the world’s finest necropolis. Here, many of the names you’ll have seen on your tour – of street names, or museum patrons, the good and bad in the literature are buried here, including the one figure that lives on, immortal, Eva Perón.

Home page photo of Recoleta Cemetery by Andrew Currie.

Daniel Neilson

Latest posts by Daniel Neilson (see all)

- RUN BA RUN - July 12, 2016

- A Beginners Guide to Football Teams in Buenos Aires - September 10, 2014

- Argentina Hit Their Stride in World Cup 2014 - June 26, 2014

Interactive Walking Tour Map of Buenos Aires Restaurants

Interactive Walking Tour Map of Buenos Aires Restaurants  Art Map of Buenos Aires – An Interactive Walking Guide

Art Map of Buenos Aires – An Interactive Walking Guide  Living in Buenos Aires: Barrio by Barrio

Living in Buenos Aires: Barrio by Barrio  The Neighbourhood of San Telmo, Buenos Aires

The Neighbourhood of San Telmo, Buenos Aires  The Best of Buenos Aires Architecture (Including Five Quirky Finds…)

The Best of Buenos Aires Architecture (Including Five Quirky Finds…)  Football Map of Buenos Aires – An Interactive Guide

Football Map of Buenos Aires – An Interactive Guide  FREEMASONRY AND BUENOS AIRES’ MOST IMPORTANT BUILDINGS

FREEMASONRY AND BUENOS AIRES’ MOST IMPORTANT BUILDINGS  Alternative Tours of Buenos Aires

Alternative Tours of Buenos Aires  BUENOS AIRES HOTELS FOR FOOD AND WINE LOVERS

BUENOS AIRES HOTELS FOR FOOD AND WINE LOVERS  Foto Ruta’s Top Alternative Photography Locations in Buenos Aires

Foto Ruta’s Top Alternative Photography Locations in Buenos Aires  Visit the Argentina of Evita & Juan Perón

Visit the Argentina of Evita & Juan Perón  Day Trips from Buenos Aires: Five Tiny Towns to Explore

Day Trips from Buenos Aires: Five Tiny Towns to Explore